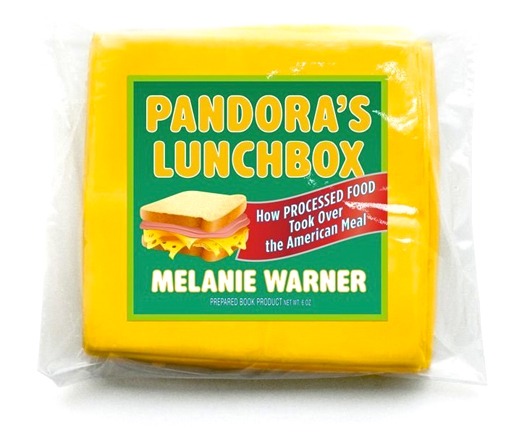

From Subway sandwiches that contain more than 100 ingredients to packaged cheese that won’t spoil for eternity, processed food accounts for 70 percent of America’s caloric intake. In Pandora’s Lunchbox: How Processed Food Took Over the American Meal, former New York Times reporter Melanie Warner explores the depths of engineered food and its implications for our health and society. We got in touch with the author to learn about her investigation to uncover the truth, her most shocking discovery, and her advice for changing the way America eats.

(Join Melanie tomorrow at noon for a special installment of our Enlightened Eaters series at the Beard House.)

--

JBF: You started out as a business reporter for Forbes and the New York Times. How did you get interested in writing about food?

Melanie Warner: I was fascinated by the sheer size and complexity of the food industry and, more importantly, by the gap between what people knew about the food they were eating and how these foods were actually produced. Food is not something that should be opaque and mysterious. In 2004, when I started writing about the industry, it was. We know a lot more about our food system now, but this awareness has only seeped into a small percentage of the population. The shift towards a more conscious approach to eating needs to go a lot farther.

JBF: What first captured your attention about processed food, and what made you steer your work in that direction?

MW: I remember talking to a food scientist who told me a scary fact about the production of vegetable oil: the factories must be explosion-proof because a highly flammable, neurotoxic chemical, hexane, is used. The fact that it’s so dangerous to produce one of our most commonly used ingredients alarmed me, and I wondered what else was happening in food production that I knew nothing about.

JBF: What’s your most vivid memory or interaction with processed food?

MW: The first time I went to the Institute of Food Technologists trade show I was blown away. There were more than a thousand companies avidly selling ingredients that most people would never recognize as food. People openly talked about how manufacturers could cut out real food items, replacing them with their cheaper, fake substitute. There was a whole different language being spoken about food, like it was a software program to be written. They prided themselves on finding ways to cut corners, and most people were more than happy to talk to me because they saw nothing wrong with any of it. Everything was hiding in plain sight.

JBF: You were already pretty well-informed about processed food before you set out to research and write Pandora’s Lunchbox. Was there anything you uncovered that truly shocked you?

MW: I was shocked to learn that the vitamin D added to both your morning cereal and the milk poured over it comes from sheep grease. I was also surprised by the extent to which many people in the food industry don’t eat their own products. I talked to many people who eat pretty close to the way I do—home-cooked meals made with fresh, organic food. If everyone ate this way, they’d be out of a job.

JBF: What do you think is the most dangerous element of processed food?

MW: The biggest problem with processed food is its over-consumption, and the fact that we regard it as a normal thing to eat all the time. Many think there’s nothing wrong with some frozen pizza washed down with a handful of Oreos. The health concerns with processed food not only have to do with what it contains—excessive quantities of sugar, sodium, fat, refined grains, and quasi-edible additives—but also with what it doesn’t: naturally occurring vitamins, antioxidants, and fiber. It’s not really about one ingredient or another. Yet if I were to highlight one or two, I’d say sugar and foods that are deep-fried in vegetable oil. Vegetable oils are inherently unstable and have a tendency to form toxic oxidation byproducts when heated.

JBF: What are some of the most common examples of processed food masquerading as healthy options?

MW: A lot of the items in the middle aisles at Whole Foods seem a lot healthier than they are. Just because someone slaps an organic label on a “toaster pastry” doesn’t mean it’s not still a Pop-Tart. I’m not sure that it’s useful to have so many “natural” versions of snacks, cereals, and cookies. In the end, I think it just steers people away from more nutritious, fresh food. For example, I’ve long felt that Subway skidded by for years on its “Eat Fresh” campaign without anyone bothering to ask what it meant. You can’t make a sandwich with 105 ingredients, with at least half of them strange and unidentifiable, and call it either fresh or healthy.

JBF: You stress the importance of simple home cooking as a way to combat the perils of processed foods, while also acknowledging that many Americans lack basic cooking skills. What’s your advice for getting back into the kitchen and away from processed food?

MW: I think we need to start with children, who are naturally curious about everything, including food. Let’s teach them how to cook and where food comes from and make it fun. I’d love to see soda taxes pay for this, perhaps as an afterschool activity or as a summer camp. Right now, so many kids are only exposed to an environment dominated by processed food, so they don’t think twice about it. We need to let them know there’s another world out there. In the book, I wrote about a program called Cooking Matters. It has free cooking classes for low-income adults, teaching them that making fresh meals is nowhere near as difficult as they think. I think that if Walmart, for example, is really serious about expanding access to healthy food, they should do something similar in their stores: free cooking classes for whoever wants to take them. The company has opened 86 new stores in food deserts, but studies show that you can’t just build stores and expect people to storm the produce aisle.

JBF: You mention in your book that you don’t expect profit-driven companies to be agents of change. However, what do you think should be done to monitor or legislate their actions? And who is responsible for it?

MW: I think that placing limits on the marketing of processed foods for kids would help parents introduce healthier foods to their children. Unfortunately, there seems to be no appetite within government agencies or Congress to tussle with the food industry on this issue. In the realm of additives, the FDA needs to do a better job overseeing the multitude of ingredients that go into processed food. There’s no reason that azodicarbonamide should be in our food supply—or brominated vegetable oil, BHA, or scores of others. Ultimately, I think that trying to regulate our way out of our national eating disorder would be like playing whack-a-mole. The industry will find a way around it. The solution rests in changing how consumers think about food and the choices we make.

About the author: Elena North-Kelly is associate editor at the James Beard Foundation. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.

-57 web.jpg)