Demanding More for Your Community

Using your voice as a chef to advocate for change

Greg SilvermanJune 18, 2020

-opt.jpg)

In our ongoing op-ed series, we’re featuring voices from the culinary community and their personal positions on the food-system issues they’re most passionate about.

Our latest piece comes from Greg Silverman, chef and executive director of West Side Campaign Against Hunger (WSCAH). Below, the Chefs Boot Camp for Policy and Change alum unpacks how his work fighting food insecurity at WSCAH is not so different from the challenges and solutions he encountered as a restaurateur, and why it's crucial that chefs use their problem-solving skills to tackle the issues they care most about.

--

15 years ago, I was a chef and multiple restaurant owner in Ithaca, New York. I focused on local ingredients and seasonal products, and tried to turn a profit without charging exorbitant prices and still serving great food. My customers deserved the best, and it was my job to make sure they got it. I started demanding better products and prices from my purveyors and used my purchasing power, my network, and my voice to get them.

At the same time, I sat on the board of directors of our local soup kitchen, and often witnessed shipments of poor products at high prices for the organization; I was outraged. I started sharing data, questioning pricing, and demanding better service. I connected with the rancher who sold me a cow a week, and she helped me get free venison from their slaughterhouse. I called up my friends who sold me coffee every week and they not only gave the soup kitchen free coffee, but also offered a machine and grinder.

To some, being a chef or running restaurants is just a job, but for so many of us, it's our chance to change the world one meal at a time. Running an organization fighting hunger is no different. Those words rang true before this global pandemic, and resonate even more now.

Three years ago, I became executive director of the West Side Campaign Against Hunger (WSCAH). WSCAH is a front-line anti-hunger organization that provides healthy food and supportive services for tens of thousands of families each year across New York City. I am proud we will distribute over 2 million pounds of food this year, of which almost 50 percent will be fresh produce! Despite the new job title, the foundation of my work is the same as when I was running restaurants. I still want my customers to get the best food, best service, and best experience when they visit. I want my staff to be able to implement ideas, and I want to make sure we are working as part of a larger community. COVID-19 has not changed those goals—our service delivery, our scale, and our safety procedures have shifted, but the mission stays true.

Last year, an estimated 1.4 million New York City residents relied on emergency food programs, including soup kitchens and food pantries. Those numbers are on their way to double in the months ahead, thanks to a global health crisis and the ongoing lack of a legitimate and truly sustainable safety net for food-insecure community members. Healthy, fresh produce and other regionally grown agricultural products are often priced too high for the New York’s front-line community-based organizations (30 percent of which have been forced to close since the pandemic started) and the food-insecure customers they serve.

WSCAH is known its customer choice food pantry model that supported a community of over 22,000 people. COVID-19 upended everything. In a matter of days, we shifted our 25-year-old free grocery store model to a street side, pre-bagged, farmers market–style model set up to ensure staff and customer safety. We began delivering pallets of pre-packed healthy food to dozens of community-based partners. We shifted our social services department to work virtually to ensure no lapse in our customer’s essential benefits, such as SNAP, Medicaid, and housing.

Each and every day we see 50 to 100 new families on top of longstanding customers. Back in my restaurant days, a 350 percent increase in new customers would have me high-fiving my team each night. But today this surge leaves me deeply concerned for the health of families and children and renews my commitment to make sure a growing community of hungry New Yorkers have the food and support they need each and every day. Sadly, WSCAH has been feeding New Yorkers as an emergency feeding provider for 40 years. That's not an emergency, it's a tragedy.

Alongside the 350 percent increase in new customers, we’ve also seen a 50 percent drop in senior customers. So we partnered with food delivery companies, such as Doordash, to get food to hundreds of food-insecure seniors. WSCAH is housed in a church, and we turned the building into a socially distanced warehouse, food packaging, and distribution facility. In some ways, it reminds me of the craziness of the busiest of Friday nights back in my restaurant days. In the heart of the storm, I know deep in my bones that we are functioning exactly where we are supposed to...feeding our community with the food and support they need, and living up to our values of dignity, community, and choice.

Last year, WSCAH took its choice model one step further by helping bring choice to agencies and providers. Just like back when I was a restaurant owner, my customers and all New Yorkers in need deserve better products and prices from our purveyors. I began assembling a local network of emergency feeding changemakers looking to disrupt an ineffective, imbalanced, and unjust system.

-opt.jpg)

Pre-COVID, we knew that the emergency food sector across the country was fragmented, under-resourced, and over-stretched as the federal government makes huge cuts to SNAP and further isolates immigrants. The Collective Purchase project helped us get healthy foods to those in highest need and set up our network to work as a team since the first days of pandemic.

Four (five since the pandemic) New York City based anti-hunger organizations came together with the support of Robin Hood Foundation, Sea Change Capital, NY State Health Foundation and now New York Community Trust with a belief that all New Yorkers should have access to more high-quality food; that we could save money; and that we could find new ways to collaborate.

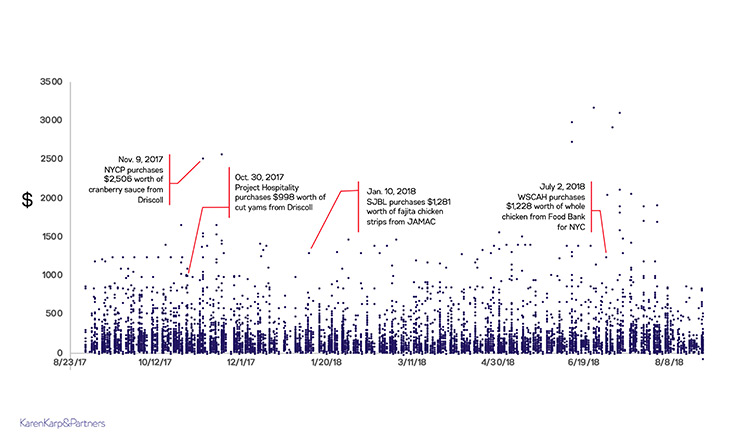

After inputting a year's worth of invoices, analyzing purchasing patterns, and negotiating with purveyors, a Collective Purchase initiative was piloted. Our team put out a report that shows that our program helped 4 of the largest food pantries in NYC save almost 19 percent on food purchases. This allows these agencies to purchase more regionally grown, fresh products, and facilitates direct collaboration and innovation.

With the Collective Purchase initiative, we get better pricing on food and built a base of cost savings to help us maximize essential dollars for our community. More importantly, we built trust and collaboration over the last year. In last two months, we have not only been ordering PPE together, but we are using our collective voice to express our thanks via an editorial in New York Daily News to our essential staff. We are also continuing to express our displeasure at the lack of transparency in city, state, and federal food related funding streams as seen in Politico. Finally, we work together to bring healthy food to those in need.

Last month we received our first delivery from the USDA Farm to Food Box program. We received 2800 twenty-pound boxes of fresh produce that within 24 hours was given out across our community along with all the whole grains, proteins, and dairy we supply. That is over 50,000 extra pounds of produce that we are hopeful will be coming in each week to go out across our network of community partners. This is pushing us to look collectively at our trucking, our refrigeration, our warehousing, and in general how we do business. Sounds familiar? If you are in the food system, you have your own version of this grappling with change, massive shift in service, and changing business models before and now during this pandemic.

As a former multiple restaurant owner I am shocked, saddened, and dismayed at what has befallen the restaurant and greater food system since this pandemic began. As a leader of an anti-hunger organization, I do not look forward to seeing the coming deluge of new customers at our “thriving” anti-hunger organization. But I do look forward to using this moment to change this system that has led to ongoing misery for our collective community.

My team and its supporters have been on the front lines for 40 years. The community we serve has known and felt isolation and hunger well before this pandemic. Our job at WSCAH, and my job as a chef, is to help force a future food system that is, like our WSCAH team, purpose-built to feed and nourish our community.

When I look back at the last year and our Collective Purchase work, it's obvious. We simply tested a mid-week special, scaled the recipe, and rolled it out onto our menu. With COVID-19, we then were forced to build entire new service delivery models to go along with that new menu item. As a chef, I have always believed in using the fewest ingredients in a dish to maximize flavor. We think the same way at WSCAH. Focus efforts to maximize results, so our community gets the most benefit from our work. Test, taste, survey, cost, scale, prep, serve, and repeat. Whether it's a new dish on your menu or a new way to shift the food system in your community, the years of work on the line prepared me and guide me in my work on the frontlines of this pandemic.

--

West Side Campaign Against Hunger’s executive director, Greg Silverman, is a chef, former multiple restaurant owner, and longtime leader in the anti-hunger movement in New York City and across the globe.

-57 web.jpg)